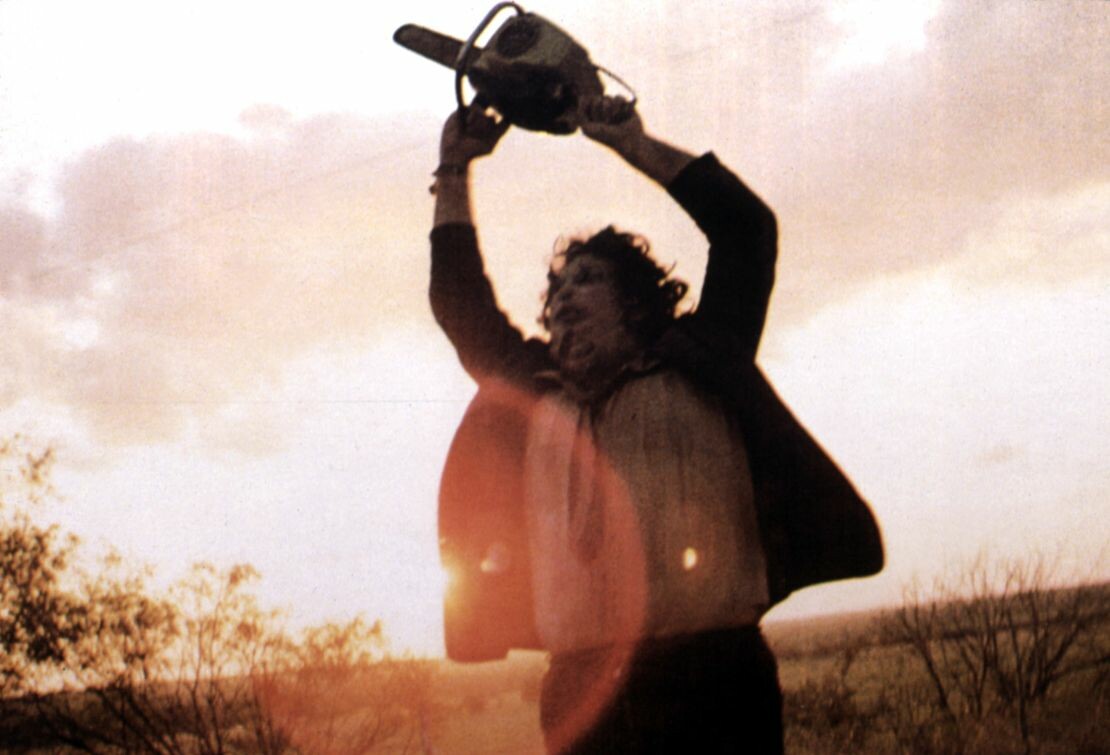

Half a Century After ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre’: Is the Classic Slasher Film Extinct or Lurking in the Shadows?

Half a century back, two visionary indie filmmakers, Tobe Hooper and Kim Henkel, conceived a film that would redefine horror. Their grim imagination birthed a tale of ruthless killings, a chainsaw-wielding maniac, a band of unsuspecting youths, and a murderous clan with a taste for human flesh. This unsettling narrative unfolded against the deceptively serene backdrop of a sun-drenched countryside that morphed into a nightmare by dusk. The duo had little more than a shoestring budget and scant recognition to propel their project forward.

In October 1974, "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" debuted in theaters, leaving audiences both horrified and fascinated. The storyline was simple, the characters even more so, but the film was drenched in a visceral grit. Despite its initial reception, Henkel revealed to CNN that the movie was banned in "numerous countries" and vanished swiftly from screens. Still, "Chainsaw" broke new ground, heralding the chaotic, blood-soaked slasher subgenre into mainstream consciousness. While the infamous shower scene of Marion Crane had occurred decades earlier, and Italian giallo thrillers had injected psychological complexity into horror, "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" introduced a raw brutality that was unprecedented.

Today, the slasher genre is a well-recognized staple of cinematic history. Yet as tastes evolve, questions linger: Is the reign of the iconic, lethal villain truly over, or does it lurk, poised for a comeback? Experiencing "Chainsaw" firsthand is essential, as mere description reduces it to a sinister tale whispered in the dark, flashlight shadows playing across faces.

The film's plot is deceptively straightforward: five youngsters trespass on the worst imaginable property and encounter a gang of cannibalistic murderers. Among them is "Leatherface," a figure with an unnerving fondness for chainsaws. The cast features a creepy hitchhiker, a girl gruesomely hung on a meat hook, and instances of graveyard desecration, all presented in a grainy, documentary-like style complete with unsettling radio broadcasts and ominous narration.

Raised in Austin, director Hooper drew inspiration from a chilling chainsaw display he saw during Christmas 1972, as he shared with Texas Monthly in 2004. The narrative elements—featuring a hitchhiker, a twice-escaping girl, and an unforgettable dinner scene—swiftly took shape afterward. Screenwriter Henkel explained that the film's savage, almost primal violence was a deliberate probe into our most profound fears. "The timeless power of German fairy tales, with their ability to evoke elemental fears, was central to our concept," he explained to CNN. "We aimed to craft a cautionary tale for our era, drawing on both conscious and unconscious anxieties, with the hope it would endure. Fifty years later, we allow ourselves a small measure of vindicated pride."

Despite its controversial nature, "Chainsaw" reached the Cannes Film Festival in 1975, amassing approximately $30 million in earnings, a staggering figure compared to the mere $60,000 Hooper and Henkel initially invested, with a fallback budget of $25,000 for a black-and-white adaptation. Not everyone appreciated its nuances, though. Film critic Roger Ebert deemed it "unnecessary," questioning the motivations behind its creation, yet acknowledged it as an "off the wall achievement" that was disturbingly effective in its intent to terrify and repulse.

Nonetheless, Henkel's prediction of its lasting impact proved true. As "Texas Chainsaw" marks its fiftieth anniversary, it enjoys screenings across the U.S., limited-edition merchandise, and reunions of its cast and crew. Comic book writer Joshua Dysart, a fervent horror enthusiast and Texan, attended a recent 50th-anniversary screening with Henkel. He recalls first seeing the film as a child in Corpus Christi, where his family was the sole owners of a VHS player on their block. The abruptness of the first kill, when Leatherface strikes down Kirk, left a lifelong mark on Dysart. "The suddenness of it was so powerful; it has influenced me as a storyteller ever since," he told CNN.

The film's formula, depicting a backwoods clan operating from a makeshift abattoir, resonated with audiences, paving the way for an entire subgenre. Following "Chainsaw," a slew of harrowing slashers emerged, heralding a golden era: "Black Christmas" shortly thereafter, "Halloween" in 1978, "Friday the 13th" and "Prom Night" in 1980, "The Slumber Party Massacre" in 1982, "Sleepaway Camp" in 1983, "A Nightmare on Elm Street" in 1984, "Child's Play" in 1988, "Candyman" in 1992, "Scream" in 1996, and "I Know What You Did Last Summer" in 1997.

Film critic and comedian Jourdain Searles, who first encountered "Chainsaw" in film school, notes that the slasher genre gradually supplanted the 'B movie.' The latter, exemplified by 1958's "The Blob," were low-budget, starless features often paired with double bills during Hollywood's golden age. Slashers, too, were inexpensive endeavors, often embedding social commentary and fostering communities among fans. "It became a new form of horror communal entertainment, allowing more violence and sexuality, and thus more room for social commentary," Searles told CNN.

For audiences, these hair-raising experiences felt both novel and familiar. The cast typically consisted of attractive, often unlikeable friends, meeting their fate at summer camps or during holiday celebrations. The methods of murder were imaginative, carried out by a masked assailant wielding sharp implements. The "final girl" was tasked with surviving the chaos by the time credits rolled.

The slasher aesthetic left an indelible mark on culture, influencing subsequent films. Icons like the Ghostface mask from "Scream" became synonymous with horror at large, while countless tropes and storylines were parodied in franchises like "Scary Movie." This trend led to a wave of remakes, including new takes on "Friday the 13th," "Black Christmas," "Halloween," and "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre."

As the prime years of slashers waned, horror diversified into various forms, with new eras embracing supernatural themes, "found footage" films, and, yes, more remakes and sequels. Contemporary horror films now lean less on camp and more on existential dread. Works like "Midsommar," "The Invisible Man," and "Longlegs" evoke thoughtful discussions about symbolism and layered meanings, adding depth to their terror.

Yet, remnants of the slasher era still resonate whenever a character ventures into a creepy basement or stumbles upon an eerie, isolated farmhouse. Dysart concedes that the slasher's dominance in the "mid-1980s," when "the horror genre was slasher," has likely passed. However, he believes the subgenre persists, as evidenced by recent films like "Terrifer 3" and "In A Violent Nature." "Each year, a few films dedicated to the slasher genre and its aesthetics emerge, achieving varying degrees of success both artistically and financially," he shared with CNN. "Nothing ever truly disappears."

Searles opines that reviving the classic slasher as it was in its golden age poses challenges. "Filmmakers today tend to overthink it. It's as if they're striving too hard to convey a message, neglecting to make it visually appealing and rewatchable," Searles remarked, noting that newer releases such as "X" and "Barbarian" lack the allure for repeated viewings.

Alex Svensson, a media scholar at Emerson College, explored the genre's complexities in his essay, "Is The Slasher Alive or Dead?: Conflicted Genre Discourse and the Continued Return of Michael Myers," for Horror Homeroom. He suggested that many anticipated a slasher "revival" following the 2018 "Halloween" installment. Svensson argues that the slasher genre is more intricate and cyclical than it appears. "A straightforward argument can be made that the slasher never truly vanished," he wrote. "It remains a persistent and enduring subgenre, even during periods when other forms of horror temporarily captivate audiences and critics."

By the time Wes Craven's "Scream" arrived in 1996, the slasher genre, as it once thrived, was "kind of already dead," according to Dysart, with "Scream" marking the inception of what he dubs the "horror deconstruction" phase. This phase, typified by "Scream," showcased a self-aware, tongue-in-cheek approach to its own genre, reflecting audiences' fatigue with formulaic slashers. The film adhered to the "rules" of horror, including a character's caution to "never have sex, never drink or do drugs," and to avoid saying "I'll be right back" if a serial killer might be lurking. A memorable scene involves Casey Becker, portrayed by Drew Barrymore, being quizzed on horror trivia by the killer over the phone.

The unique messages intrinsic to iconic slashers often distinguish them from their counterparts. Some are innovative, while others, like Craven's "Scream" and "New Nightmare," reflect on their place within the larger canon. "To create a slasher with value, you must convey the violence in a way that communicates something," Dysart explains. "The horror genre, and by extension the slasher, represents a struggle against the forces of the universe."

As countless individuals don Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees masks this Halloween, they may lament the classic slasher's once-dominant yet enduring presence in horror... all while wisely avoiding any chainsaws.